German offshore wind power - output, business and perspectives

Quick facts

Quick facts

(Figures for end of 2022; Sources: BWE, BWO, Fraunhofer ISE, WAB)

Number of turbines installed: 1,539

Total capacity installed: 8.1 GW

Projected expansion: 30 GW (2030)

Share in net power production: 5 %

Output: 24.75 TWh

Employees: ≈21,400 (2022)

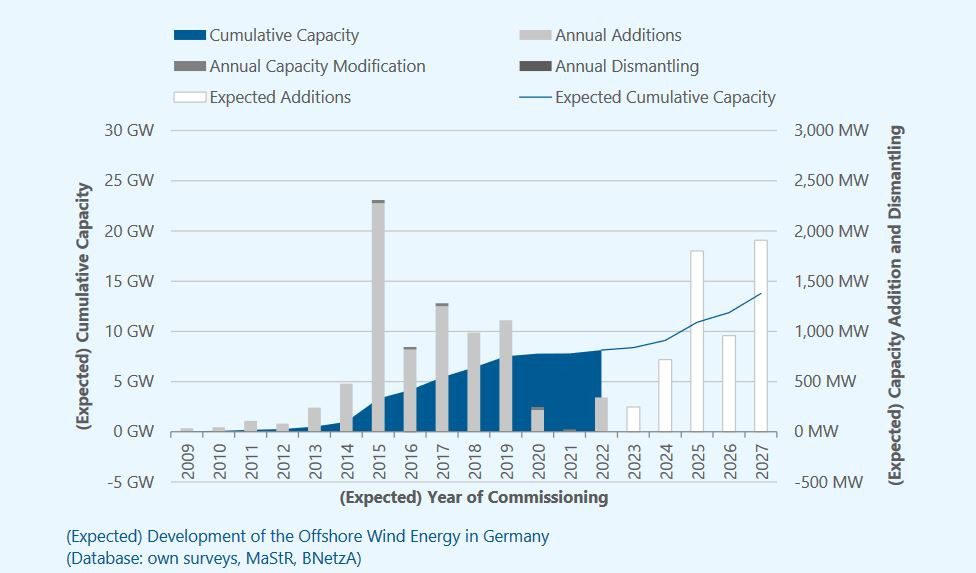

The first offshore wind farm in Germany came into operation in 2010, making it the most recent major renewable energy technology to enter the country’s electricity generation mix. In the years following its roll-out, offshore wind power saw a rapid growth in Germany and other countries around the North Sea and the Baltic Sea. At the end of 2022, more than 1,500 turbines with a cumulative capacity of roughly 8 gigawatts (GW) operated in German waters. Thanks to the turbines’ reliable performance and fast cost reduction, the first projects that no longer needed state support were announced by investors in 2017, raising hopes that the technology can become a pillar of the country’s energy transition.

Despite offshore wind’s promising potential and the government’s ambitious targets of achieving a total capacity of 30 GW by 2030, Germany did not add a single new turbine in 2021 – installing just under 40 new wind power generation hubs in 2022. This means Germany has less than eight years to almost quadruple its offshore capacity if it is to meet its targets. This endeavour therefore requires ‘turbocharging’ expansion, no later than 2025, industry representatives have said. An ‘offshore realisation agreement’ made by the government and grid operators in late 2022 marked a first step in this direction by updating previous agreements on the designation of marine areas, nature conservation requirements, timetables, interim targets and other issues.

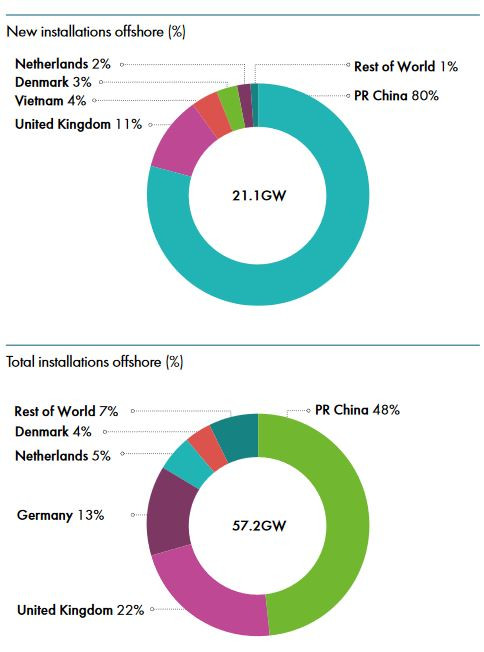

Offshore wind’s contribution to Germany’s power production mix reached five percent in 2022, a significant increase from merely 0.1 percent in 2014. As of 2019, the country was the third largest market after the UK and China, but consecutive failures to uphold strong expansion caused Germany to slide in buildout rankings. While turbines in German waters accounted for 40 percent of global capacity in 2017, the share was reduced to only 13 percent in 2021.

Grid stabilisation and industry contracts elevate offshore wind's role in energy system

Shortly after taking office, Olaf Scholz’s government announced the aim to bring the share of renewables in the power mix to 80 percent by the end of the decade, from nearly 45 percent in 2022. Continued falls in the cost of offshore wind, and the turbines' increasingly high and reliable yields have bolstered confidence that the technology can become a pillar of the German energy system. The government aims to install 70 GW of wind capacity in German waters by 2045. German waters would allow up to 82 GW of offshore wind power without infringing on other uses of German waters, such as environmental reserve zones, according to an analysis conducted by the research institute Fraunhofer IWES.

The rollout of offshore wind power in Germany has been fraught with concern about the potential impact on marine ecosystems since the first installations appeared in 2014, even though most environmental groups agree that offshore wind power is needed to meet international climate targets. An area development plan published by the Maritime and Hydrographic Agency (BSH) in early 2023 aims to lay the groundwork for the planned expansion. The plan defines specific areas for wind energy, specifies the parameters of the tendering process, commissioning, and the required grid connections.

With an average capacity of 9 megawatts (MW) and an average rotor length of 167 metres in 2022, new offshore turbines are not only grown in size and capacity significantly than when they launched in the early 2000s, but they are also bigger and more productive than their onshore counterparts. The growth in size and output has been a key to the falls in power generation prices in recent years. Harvesting the power of strong, continuous winds at sea, they deliver electricity to the grid almost all year round, producing nearly twice as much power as land-based turbines, according to wind power consultancy Deutsche Windguard. In fact, offshore power generation has proven to be so reliable that grid operators started using the turbines in 2022 to stabilise the country's electricity system in case of grid fluctuations, a role that has thus far had been reserved for fossil power plants.

In early 2023, a consortium of consulting firms put forward a joint paper proposing subsididies for reliable offshore electricity for industry customers through an auction scheme, which is intended to shield companies from rising electricity costs. After industrial companies and wind farm operators agree on so-called ‘contracts for difference’ and take part in auctions, the government could then step in to pay the difference between winning bids and the power price. However, the introduction of this system could take time, with legal implementation possible "in 2024 at the earliest,” the paper said.

Grid bottlenecks particularly challenging for offshore turbines

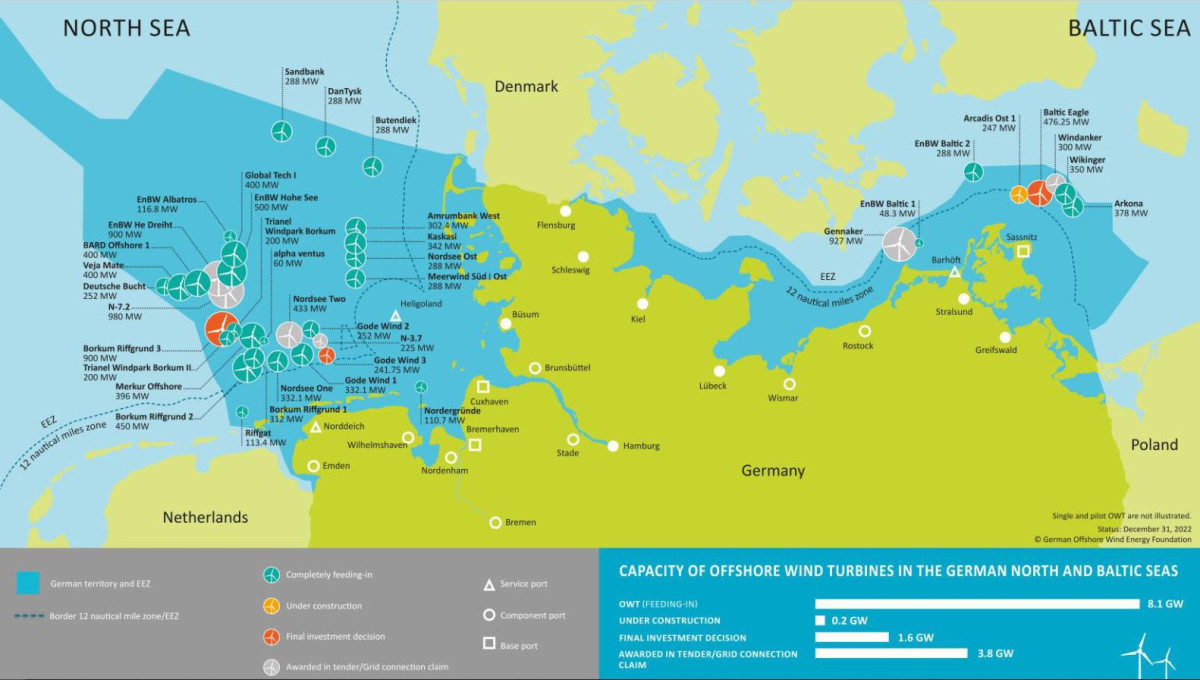

The vast majority of Germany's offshore turbines are located in the North Sea, with about 7 GW installed off Germany’s western coast, compared to just over 1 GW in the Baltic Sea to the East. Wind yields on average are much higher in the North Sea than in the Baltic, attracting investors with higher prospective returns. Future expansion is therefore set to take place primarily in the North Sea, the region where other projects from the UK, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany together have created the largest offshore wind power cluster in the world.

A 2019 study by energy policy think tank Agora Energiewende found the amount of energy offshore turbines are able to generate falls considerably if wind farms are located too close to each other. In order to spread turbines more evenly in German waters, the government has set a quota for the total number projects in the Baltic Sea being auctioned in the offshore wind power auctions. Lower Saxony, Germany’s north-western federal state on the North Sea, which also hosts most of Germany’s onshore turbines, was home to well over half of all German offshore wind farms in 2022. Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost state that borders both the North Sea and the Baltic, boasted about one third, while north-eastern Mecklenburg- Western Pomerania on the Baltic had about 15 percent of installed capacity.

The clustering of power generation capacity in north-western Germany creates challenges for providing sufficient grid capacity to transmit large volumes of electricity elsewhere in the country. Around four percent of the total renewable electricity generated in Germany in the first half of 2022 was unusable due to the grid’s lack of transmission capacity. Most electricity production losses occurred in Lower Saxony and one sixth of the total potential of offshore wind production remained unused. More connections were under construction at the end of 2022, but the government's push for more offshore power means that the schedule for linking capacity has to be revised, the BWO said.

Transmitting electricity from wind farms at sea to the mainland, however, is only one part of the problem. Another — and perhaps even bigger challenge — is to cover the much longer distance from windy northern Germany to industrial centres in the south, which the Federal Network Agency (BNetzA) has outlined in its offshore grid-development plan. The major transmission line projects, SuedOstLink and SuedLink, are now scheduled to start operation from 2027 and from 2028 respectively, after years of delay due to local protests, lawsuits and disagreement between Germany’s states over the routing. While a ‘groundbreaking’ settlement with landowners affected by the 700-kilometre powerline was reached in late 2022, industry groups in southern Germany have said the delay is starting to cause severe risks to the region’s growth prospects, especially since the sudden cut in fossil fuel supply from Russia and the closure of nuclear power, which had been postponed to April 2023, further tightened the supply situation. [See the CLEW dossier on Germany’s power grid for background].

Neighbouring countries link energy policy with joint offshore wind projects

The enormous potential of offshore wind power as a pillar of a decarbonised energy system has led many states in Europe and beyond to greatly ramp up their expansion plans, with northern Europe leading globally in offshore turbine deployment. International cooperation in the sector has been particularly strong, with Germany maintaining offshore wind partnership schemes with virtually all other countries bordering the North Sea.

In 2022, together with Belgium, the Netherlands and Denmark, Germany agreed to expand offshore wind power generation capacity tenfold to at least 150 gigawatts (GW) by 2050. The so-called “NordLink” cable, which entered into operation in 2021 with a capacity of 1.4 GW, is helping to fill Norway's hydropower stations using excess German offshore wind power, thereby increasing supply security and price stability in both countries. Offshore wind also plays a key role in linking German and French energy and climate policy plans, as both countries vowed to jointly improve their use of the technology in order to achieve competitive electricity prices and to scale up hydrogen production. With the UK, cooperation on offshore wind and other energy measures has intensified in the years since the British decision to leave the EU, defying a trend towards looser cooperation in many other policy areas. Germany also hopes to intensify cooperation on joint offshore wind use with neighbours in the Baltic Sea, a region where its insistence on the now defunct gas pipeline Nord Stream 2 linking it with Russia has cost Germany a lot of diplomatic capital in energy policy after Russia’s attempted invasion of Ukraine.

As many turbines are built far away from the coast, with new installations in German waters being located some 70 kilometres offshore on average, generated power is usually converted into direct current on-site in order to minimise transmission losses before it is transferred to the nearest node on land. A substation bundles the output of all turbines in a wind farm and converts the power produced to a different voltage level. To improve on-site processing of generated electricity, several European grid operators have proposed to build at least ten artificial “energy islands” as wind power hubs in the North Sea to make use of large-scale offshore wind energy in meeting the continent’s climate targets.

According to the North Sea Wind Power Hub consortium, a possible trans-border offshore grid project between Denmark, the Netherlands and Germany could play an important role in these countries’ energy systems. By removing the need for individual substations in a central location at sea, the islands could substantially reduce costs for offshore wind power installations. In 2020, Germany and Denmark agreed to intensify cooperation on these offshore ‘energy hubs’. Other initiatives to better integrate offshore wind power into the joint European power grid include ‘Eurobar,’ a joint project by seven grid operators to interconnect offshore wind platforms.

Zero-support wind farms have spurred investors' interest

The wind farms’ distance from the shore and the often harsh conditions at sea, where heavy waves and saltwater require special equipment and training for workers, have historically been a major deterrent for investors. According to the German ministry for economy (BMWi), commercial banks were reluctant to finance pioneer projects as the financial risks were hard to gauge. Germany initially helped investors close funding gaps with financial assistance from the state-owned development bank KfW, which funded the country’s first ten offshore projects at customary interest rates. The five-billion euro programme by the KfW was therefore intended to allow operators who were willing to take a financial risk to gather experience and sound out cost reduction potentials.

Yet, continually high yields and steep learning curves have led to improved procedures and falling costs, which in turn greatly increased offshore wind power’s attractiveness for investors. A study by the Hertie School of Governance found that budget planning made significant improvements in offshore wind projects: while the country’s first offshore farm, Alpha Ventus, overshot cost projections by some 30 percent, financial planning subsequently was made more accurate. The average cost overshoot of Germany’s offshore wind farms has been reduced by around 20 percent, the researchers found, with much of the additional costs due to lagging grid connection. By contrast, nuclear plants overshoot estimated costs on average by 187 percent, the study found.

Initial support rates in the form of guaranteed remuneration for operators 2014 were 15.4 cents per kilowatt hour (kWh) over a period of 12 years or 19.4 cents/kWh over eight years in order to lure investors. After this period, the support rate paid by customers as a surcharge on their power bill falls to a basic level of 3.9 cents/kWh and ends after 20 years of support. Guaranteed support for new offshore turbines was already gradually decreasing when Germany’s renewable energy support scheme switched to auctions in 2017, a move that was followed by substantial cost reduction results and some operators even announcing to launch projects without any direct support payments at all.

The average support level in the first auction was 0.44 cents/kWh which, according to the German Wind Energy Federation (BWE), has made the cost question much less relevant. In the second auction in April that year, however, average support levels surged to 4.66 cents/kWh, although some bidders again offered to build for 0 cents/kWh. Bids in an auction which ended in September 2022 were capped at 6.4 cents/kWh. According to industry association AGOW, the higher average support rate is mostly due to the so-called "Baltic quota," which ensured that projects in the less productive Baltic Sea took precedence over those in the North Sea to lower competition between the regions. In an auction which concluded in September 2022, energy company RWE successfully applied for another zero-support project. According to Germany’s grid agency BNetzA, this is proof that operators today are confident they can run their turbines at a profit.

Jobs in offshore wind largely safe, but industry calls for continued support

As more and more offshore turbines have been built in recent years in the North Sea and the Baltic Sea, employment in this highly specialised industry sector has been steadily increasing. Figures by industry association WAB from early 2022 said that around 21,400 people were directly employed in the industry, generating an annual turnover of 7.4 billion euros. Employment in the sector would to a great extent depend on political decisions, especially regarding projected expansion levels that provide planning security for investors, WAB said. However, lack of skilled workers who can install, operate and maintain renewable power infrastructure has emerged as a general challenge for Germany’s energy transition.

While offshore wind is creating jobs for bearing, gearing and generator producers across the country, industry in the coastal regions is benefitting the most from the technology’s rise. Ports on the North Sea and the Baltic, such as Bremerhaven, Cuxhaven and Rostock, are upgrading their capacities to host giant turbine components, foundation systems and mounting equipment. However, observers have warned that insufficient port capacities and construction vessels could become bottlenecks for the revised 2030 buildout.

Shipyards and service providers that cater for maintenance and wind farm operating personnel add to those profiting from the expansion boom at sea, according to the Offshore Windenergie Foundation. German North Sea outpost Heligoland, a small island situated some 65 kilometres offshore, is hoping to unlock even more offshore wind potential by meeting the anticipated green hydrogen boom, which utilises wind energy to produce storable fossil-free fuel on-site.

Siemens Gamesa, Germany’s largest turbine maker, was formed by a merger between the wind power branch of German engineering heavyweight Siemens and Spanish turbine manufacturer Gamesa, which according to Bloomberg lost its leading position to Chinese manufacturers in 2022. The switch to auctions in Germany’s renewables support scheme has compounded cost pressure for turbine makers, which already caused companies like Nordex and Senvion to lay off staff. Siemens Gamesa said it also needs to cut jobs internationally due to a fall in global revenue.

However, according to a survey among employee representatives by labour union IG Metall, jobs that are focused on the offshore sector will be less affected by the companies’ austerity plans. Most of those surveyed say the prospects for offshore wind are better than those for the German wind power industry as a whole. Yet despite the relatively comfortable circumstances enjoyed by the offshore wind industry, local politicians and industry representatives are calling on the federal government to ramp up its offshore plans due to the technology’s cost drops and reliable power supply. In their ‘Cuxhaven appeal’, lawmakers from northern Germany and wind power company leaders say rigorous support of the technology has been responsible for lower prices and is still needed.